Writer to Writer: Ashley M. Jones

Writer to Writer is a guest blog project from Girls’ Club writer in residence Jan Becker that focuses on local writers and their perceptions of how femininity and self-proliferation figure into their work.

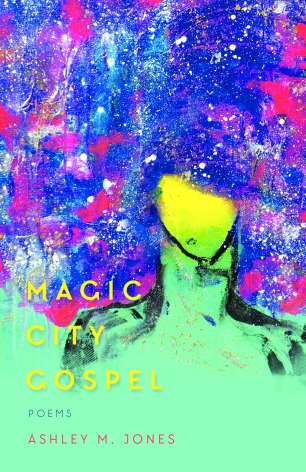

Ashley M. Jones received an MFA from Florida International University. Her work has been published by the Academy of American Poets, pluck!, PMSPoemMemoirStory, Prelude, Kinfolks Quarterly, and other journals. She received a 2015 Rona Jaffe Foundation Writer’s Award and a 2015 B-Metro Magazine Fusion Award. She is an editor of [PANK] Magazine, and she teaches creative writing at the Alabama School of Fine Arts. Her forthcoming debut collection of poetry is Magic City Gospel (Hub City Press; 2017) an exploration of race, identity, and history through the eyes of a young, black woman from Alabama.

For this interview, Girls’ Club Writer in Residence, Jan Becker, talked with Jones about the Magic Cities of Birmingham, Alabama and Miami, Florida, the good spell of poetry, the importance of history, how word magic impacts young people and the world at large, and how she’s coping with a year packed with new opportunities and accolades.

JB: Ashley, thank you for talking to me for the Girls’ Club blog about your work, and your forthcoming debut collection of poems Magic City Gospel (Hub City Press; 2017). I’ve read an advanced reading copy of the book, and I’m very excited to talk about it with you, because I think it’s an important book. I want to start this interview by deconstructing the title of your book, and talking about how place figures into your writing. First, the Magic City of the title is Birmingham, Alabama, where you grew up and live now. But I’ve also heard people call Miami the “Magic City.” You spent some time here in South Florida, especially in the MFA program at Florida International University in Miami while you were writing these poems. Can you talk a little about what makes each of these places a “Magic City?” Did Miami’s magic make it into your book as well?

AJ: Yes! Miami’s magic most definitely made it into this book—in fact, I wouldn’t have appreciated my own Magic City (Birmingham) if I hadn’t moved to Miami. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

Place is so huge in this book—Birmingham as place, memory as place, blackness as place. This would be a completely different book if it were written by a non-Birminghamian, by a non-Ashley M. Jones, by a non-black person. These histories I deal with are directly related to the where and when. I wouldn’t react to a KKK uniform in a museum the same way if I weren’t a black girl from Alabama. I certainly wouldn’t react to the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in the same way—I mean, the fact that I literally could have been one of those girls is a sobering reality, and it makes me, as a poet, interact with that historical material in such a personal way. As far as what makes Birmingham magical, that’s a hard question to answer. Perhaps it’s our history that makes us magical—we popped up on the scene with iron ore, we stayed on the map because we championed racism in our laws and our deeds, and we remain in a sort of spotlight because some people say we’re an example of how far a place can come. Yes, we’ve progressed—although I wasn’t alive during the days of Jim Crow, I do feel like things have changed, positively, although I hesitate to quantify it. We are certainly not “post-racism” in Birmingham, and don’t let anyone tell you that we’re a shining example of how to completely recover from social injustices, because we’re still dealing with these issues today, but I will say that our magic does lie in these contradictions and struggles and joys, and the incredible future we can enjoy if we don’t throw our past transgressions into a “that was then” pile.

As for Miami—that city’s magic isn’t what people think it is. There are lights and sparkling celebrities, expensive cars and loud music, and the whole place is this sort of colorful explosion that sets your pulse beating fast. But! I found magic in Miami in poetry, in young artists, and in the way the community seems to always be down for something weird and artsy. It takes a certain amount of vulnerability, whimsy, and trust for a city to open itself up for a whole month of poetic activity (O, Miami Poetry Festival – or, Poetry Christmas if you ask me), and that is magical to me. It wasn’t until I left the South (because we all know Miami isn’t in the South. It is clearly doing its own thing. Y’all don’t even eat grits!) that I realized how much magic can exist in one place. Seeing the vibrant culture of Miami, and the way little things can really be so poetic and tragic at the same time—I mean, a city that will, eventually, be underwater is constantly constructing, reinventing, celebrating a poetic exercise in carpe diem, I think—really made me yearn to reconnect with my hometown and find those tragically magical things that I interacted with on a daily basis in Miami. And, you can’t really appreciate a place until you’re away from it, and that’s exactly what happened when I left Birmingham, and somehow found myself in the other Magic City. Even that shared nickname seemed to tell me I needed to hasten back to my own magic instead of borrowing Miami’s. I’m forever grateful for those three years in Miami, though, because they awakened an idea that every little thing, every little place, even the way the air is so hot it looks like water, can be absolutely magical, and can take me to the page and beyond.

So, short answer: yes, Miami is also a huge part of this book. Being there, away from my home, actually made me closer to home and all its magic. I had to fill those 800 miles with poems, and that versebridge is this book, Magic City Gospel.

JB: My next question again is more deconstruction of the title. This time, I want to focus more on the “Gospel,” because to me, “Gospel” is a word that’s loaded with meaning. There’s the music of course, the four books in the Bible—also sometimes referred to as the “Good News,” but then it goes deeper also, into ideas of irrefutable “truth,” and of spreading knowledge to a wide audience. Out of curiosity, I looked into the etymology of the word, and it’s very literal translation comes from Old English for “good spell.” I think it’s a fair assumption, based on your work with children, and from reading your poetry, that words are not something you believe exist in a vacuum—that they change things when they’re let loose on the world. So here’s the big question, what kind of magic, if you take the title very literally, are you hoping to let loose in the world? If this is a good spell, what do you want it to do?

AJ: I am absolutely in love with the idea of gospel as a good spell. That’s exactly what it is, I think. And, you’re right, words absolutely do not exist in a vacuum. They have so much power, and they do change things when they’re let loose in the world or let loose in a student or a reader. And, if I’m going to let any words or spells loose in the world, I only want them to be good ones. That doesn’t mean they’ll be all cotton candy and kumbaya. In fact, I think some of the best “good spells” are those that make you uncomfortable, that make your brain all itchy with wonder and your heart all drippy with the most viscous emotion you can bear. But, joy is also a wonderful magic to spread. We need both—joy and pain, in the immortal words of Frankie Beverly. I want to spread the magic that is my own self-celebration. That I come from a place (Alabama, America) where they were hosing people down and bombing their homes and lynching their mothers because of the same skin I’m wearing today, and that I grew up learning about that history, and that I’m living in a world that’s, I guess, a little craftier in its delivery of discrimination (not always so crafty, sometimes it’s the same old thing), but I still want to celebrate it and the me that it produced is something quite magical and powerful. I refuse to forget what this place went through and what it’s going through, and I refuse to forget what I’ve been through, but I’m still in love with me and with Birmingham, flaws and all. I want to spread that history to those who don’t know it, and to those who know it too well but maybe haven’t heard it from this perspective. I want to show young writers that they can write about themselves, their little hometowns or big hometowns, little histories, big histories, or the way their dad painted Santa Claus brown, or the way their mom would only buy them black and brown dolls, or how they still think about the unibrowed boy who rejected them in fifth grade and it is still powerful and it is still poetry and it is important.

JB: I want to focus on the history of Birmingham for a moment, because it has had such an important role, not only in the history of the United States, but also specifically in the history of The Civil Rights Movement, and many of these poems are strong considerations of how history impacted both you, and many generations of Black Americans. It’s obvious that as a country, we still have a lot of work to do in areas of personal liberty and equality. Can you talk about what America at large can learn from Birmingham?

AJ: This is the question I hate to answer, because although I’m very proud of what Birmingham has left behind—Bull Connor, “segregation now, segregation forever,” a police force full of KKK, etc… I’m super hesitant to say that we’ve done it, or that we’ve solved every single problem, or that those problems can neatly fit into “the sixties” or The Civil Rights Movement, because they can’t. As a country, we have made some strides—and they’re not small ones. It’s sad that we have to do so much work to let humans live as humans on earth, but that’s a discussion for another day, perhaps. Like America, Alabama has made a lot of strides in the areas of personal liberty and equality, but there are still many issues we need to address. I will be slow to adopt a hashtag or call the civil rights struggle a past issue, but I will say that we are moving in a positive direction. The issue was always larger than just water fountains and lunch counters, but that I can exist in this city and walk freely and proudly, and that I am a Black professional, that I’m visible to students and to my peers, and that I’m being recognized for work that is completely concerned with blackness and womanness and the broken history/present of Birmingham and America means quite a lot. And, more importantly, the fact that I’m not alone in this visibility means a lot, too. The fact that I can go to AWP or read a list of contest winners or literally open any contemporary journal publishing quality work and see so many of us who are so often silenced is an encouraging thing. Again, not saying all problems are magically solved, but that is encouraging. I think America can learn about the horrors of human insecurity and the poison of power structures from Birmingham. That a whole city can be set up, from the ballot box to the governor’s mansion to the dude directing traffic to even a waiter making sandwiches from plain white bread and cold bologna, to oppress, exclude, deny, dehumanize, and control a race of people is horrific and almost unbelievable. We are seeing that sort of fear, insecurity, and inability to see past a need for power start to creep out over our country (or, if I’m being honest, it’s just being dragged out more. It was never dead, just hiding, although sometimes in plain sight.). Again, although I don’t want to say that Birmingham is some sort of picture of perfection and equality, we can look back and see that those methods do not win in the long run, and that they create so many problems and setbacks, and you just look terrible if you’re driving a tank through your city in the name of segregation. Or building a wall.

I think Birmingham is really becoming a beautiful and modern city, and it’s becoming a place that is magical to everyone—not just people who were born here. Just a few weeks ago, I was eating at Post Office Pies in Avondale, which is a sort of gentrified area now, and when I found out that this place was owned by a black man who was actually from the area, my heart did backflips. That’s the way to pour your talents back into your hometown. That’s what Birmingham is experiencing right now. Those of us who grew up in a slightly less international/shiny Birmingham are coming back with our knowledge from all corners of the world, and we’re trying to build the city into something even more magical than it already was. That’s what our future can hold. And America is no different. We need to pour into the country and into each other, and discourage this toxic, horrific climate that’s edging in. We need to talk about race, privilege, economic disparity, the apathy of some of our lawmakers, and all the rest. We have to dig in—this generation will have incredible power, just as it has in Birmingham.

JB: Over the last year or so, you’ve graduated from FIU, moved back to Birmingham, and began working at the Alabama School of Fine Arts. That’s a lot, but then you also took over as co-editor of [Pank] Magazine, signed a book deal with Hub City Press, and won a Rona Jaffe Foundation Writer’s Award, which is a huge honor. Can you talk a little about what the past year has been like for you as an emerging writer?

AJ: This past year has been unreal. And, it’s also been an exercise in humility. It is completely unheard of that I’d experience this much success in such a short time and so soon after graduating with my MFA. I am so incredibly humbled to know that my words are doing so much in the world already—my words! It has been wonderful and life-affirming to cross so many things off my poet’s to-do list, but I have also had to remember that I can’t let this sparkly year go to my head or make me feel pressured to always have this sort of Grand Slam year. I’m beyond honored to be valued by the literary community and to be entrusted with these incredible students at ASFA and to be considered literarily responsible enough to co-edit [PANK], but, I’m also having to give myself little pep talks here and there so I realize I don’t have to be a literary superhero all the time. Yes, I have students looking at me and looking up to me. Yes, I’m an editor, and I’m choosing work that I hope will impact people and mean something in the world. Yes, I was a Rona Jaffe Writer’s Award winner, and that’s something to be super proud of. But, I’m also allowed to be Ashley who likes to veg out and watch Bollywood and sometimes not write poetry. This many good things can sometimes be paralyzing—you don’t want to mess up or fall from this poetic mountaintop, but I’ve had to spend this year enjoying the successes, but also realizing that my work and my life will still matter even if I never win anything ever again.

On a less philosophical note, this year has really made me feel how small the literary community really is. There are less degrees of separation between me and my literary heroes than I thought, and that’s very encouraging as a writer. I feel like, when I go to the page, realizing that this blank page is just as blank for me as it is for, maybe, Kevin Young or Tracy K. Smith is comforting, and it makes me a lot less judgmental of my work. I’m a poet just like they are poets. I have trained, I have seen things, I have literary creativity just like they do. I can get up in front of a class and wax poetic about verbs just like Campbell McGrath does. I can go to a conference and shake hands with the editor of RHINO. I can see my name and my poem on poets.org. I can do all of those things and I can still sit in anguish at the blank page just like they do, and in that (and so many other things) we are connected, and it makes some of that paralysis I referenced earlier a little less present.

JB: Lastly, I want to ask you about your work with young people. When you were here in South Florida, you were actively involved in the Little Free Libraries Initiative in Sunrise, and served as its Official Poet. Now that you’re back in Birmingham, you teach at a school for fine arts—where you were also a student. Can you talk about the positive impact you’ve seen poetry having on young people and how the “gospel” of poetry spreads once young writers begin creating poems?

AJ: Oh, students are my absolute favorite. There’s really nothing more exciting and scary and rewarding and frustrating and magical than working with students. In Miami, I worked with very young students (second graders) all the way up to high school students and first-year college students. I saw, even in the really young ones, the confidence poetry seemed to bring. The students found voice and something sparkly that made them puff up their chests when they shared work after a workshop. Some students wrote about their pain, and that was a cathartic experience as well, for the writer and the listener. Most importantly, I think these students realized what a beautiful story their lives held, and even if they never wrote another poem after I taught a Saturday workshop or came to their school for an afternoon, I could feel and see something click in them when I told them to write about themselves and their experiences. The world becomes a magical place when you realize that something as small as butter can be poetic (with thanks to Elizabeth Alexander, of course). In Birmingham, that same thing is happening, but there’s another element here because these students I’m working with at ASFA (Alabama School of Fine Arts) are doing an intensive, six-year-long course of study, so they are learning skills that will eventually propel them to an MFA, to a Pulitzer, to a career in writing. Seeing them realize that they have what it takes to make it that far, that they have a unique opportunity to dive into their career right now, in junior high and high school is magical for them and for me. When they discover what they can do with punctuation, or when I introduce them to a new writer or show them what political work can do in a book like Citizen [by Claudia Rankine], they let that knowledge bleed into their work, and then that bleeds into other students’ work, and that excitement makes them work harder to make their writing strong, and that strength is then recognized in journals and contests, and they’re seeing their literary dreams come true, and they’re even more empowered to keep writing and spreading that literary gospel. And, if all of that can happen because I write and I believe in my work and the power that writing can have in someone’s life, I am happy to keep writing and teaching and spreading whatever poetic gospel I can!

How to Make Your Daughters Culturally Aware and Racially Content During Christmastime, by Ashley M. Jones from Magic City Gospel (Hub City Press; 2017)

How to Make Your Daughters Culturally Aware and Racially Content During Christmastime, by Ashley M. Jones from Magic City Gospel (Hub City Press; 2017)

Previously appeared in PMSPoemMemoirStory

Remind them

Jesus Black.

Despite the pictures Granny

has hung on the wall,

despite the glowing good old boy

on her pile of church fans,

Jesus was a brother.

A bruh, not a bro.

Hair of wool, you tell them.

Buy a new nativity set.

Mary with her press and curl,

Joseph with a fade,

baby Jesus fresh out the womb

and curly.

Go to a roadside Christmas shop.

Buy a pale, smiling Santa.

Let your daughters wonder

how he turned brown overnight—

how Santa’s face became just like their own,

brown and buttery, a Yuletide miracle.

When you’re trimming your plastic tree—

the one you’ve had since the 80’s,

put on “Rudolph” bopped by the Temptations,

“Deck the Halls” by Smokey,

Donny Hathaway’s “This Christmas,”

and Gladys Knight’s deep, brown voice crooning “Jingle Bells.”

Fill the treeskirt

with tightly-wrapped gifts.

31

Anticipate

your daughters’ unbreakable smiles

when they rip off the paper

to reveal an army

of Black Barbies

and brown baby dolls.

About Writer in Residence Jan Becker

Jan Becker, local writer and poet, has been selected as Girls’ Club 2015/2016 writer-in-residence. Becker will work collaboratively with Girls’ Club to present various public programs and contribute writings in conjunction with the exhibition Self-Proliferation, curated by Micaela Giovannotti.

Jan Becker was born in a small coal-mining town in Northeastern Pennsylvania, and subsequently grew up in a Marine Corps family on military bases all over the United States. She completed her BA in English, Creative Writing and Rhetoric with a concentration in Global Cultures at SUNY Binghamton, where she was awarded the Andrew Bergman Prize in Creative Writing, and the Alfred Bendixen Award for her creative honors thesis.

She is currently an MFA candidate at Florida International University, where she is focusing on creative nonfiction for her thesis. At FIU, she’s taught courses in composition, technical writing, creative writing and poetry. She has also taught poetry and nonfiction workshops with Reading Queer and First Draft with the Center at MDC.

In 2015, she won an AWP Intro Journals Project Award for creative nonfiction. Her work has appeared in the Florida Book Review, WLRN, Emerge, Sliver of Stone, and Circus Book, among other places, and is forthcoming in the Colorado Review. She has also been a regular contributor to the online photography and writing project Selfies in Ink, and is a freelance copywriter and editor.